Thinking in Java, 3rd ed. Revision 4.0

[ Viewing Hints ] [ Book Home Page ] [ Free Newsletter ]

[ Seminars ] [ Seminars on CD ROM ] [ Consulting ]

It’s a fairly simple program that has only a fixed quantity of objects with known lifetimes.

In general, your programs will always be creating new objects based on some criteria that will be known only at the time the program is running. You won’t know until run time the quantity or even the exact type of the objects you need. To solve the general programming problem, you need to be able to create any number of objects, anytime, anywhere. So you can’t rely on creating a named reference to hold each one of your objects:

MyObject myReference;

since you’ll never know how many of these you’ll actually need. Feedback

Most languages provide some way to solve this rather essential problem. Java has several ways to hold objects (or rather, references to objects). The built-in type is the array, which has been discussed before. Also, the Java utilities library has a reasonably complete set of container classes (also known as collection classes, but because the Java 2 libraries use the name Collection to refer to a particular subset of the library, I shall also use the more inclusive term “container”). Containers provide sophisticated ways to hold and even manipulate your objects. Feedback

Most of the necessary introduction to arrays is in the last section of Chapter 4, which showed how you define and initialize an array. Holding objects is the focus of this chapter, and an array is just one way to hold objects. But there are a number of other ways to hold objects, so what makes an array special? Feedback

There are three issues that distinguish arrays from other types of containers: efficiency, type, and the ability to hold primitives. The array is the most efficient way that Java provides to store and randomly access a sequence of object references. The array is a simple linear sequence, which makes element access fast, but you pay for this speed; when you create an array object, its size is fixed and cannot be changed for the lifetime of that array object. You might suggest creating an array of a particular size and then, if you run out of space, creating a new one and moving all the references from the old one to the new one. This is the behavior of the ArrayList class, which will be studied later in this chapter. However, because of the overhead of this flexibility, an ArrayList is measurably less efficient than an array. Feedback

In C++, the vector container class does know the type of objects it holds, but it has a different drawback when compared with arrays in Java: The C++ vector’s operator[] doesn’t do bounds checking, so you can run past the end.[51] In Java, you get bounds checking regardless of whether you’re using an array or a container; you’ll get a RuntimeException if you exceed the bounds. This type of exception indicates a programmer error, and thus you don’t need to check for it in your code. As an aside, the reason the C++ vector doesn’t check bounds with every access is speed; in Java, you have the constant performance overhead of bounds checking all the time for both arrays and containers. Feedback

The other generic container classes that will be studied in this chapter, List, Set, and Map, all deal with objects as if they had no specific type. That is, they treat them as type Object, the root class of all classes in Java. This works fine from one standpoint: You need to build only one container, and any Java object will go into that container. (Except for primitives, which can be placed in containers as constants using the Java primitive wrapper classes, or as changeable values by wrapping in your own class.) This is the second place where an array is superior to the generic containers: When you create an array, you create it to hold a specific type (which is related to the third factor—an array can hold primitives, whereas a container cannot). This means that you get compile-time type checking to prevent you from inserting the wrong type or mistaking the type that you’re extracting. Of course, Java will prevent you from sending an inappropriate message to an object at either compile time or run time. So it’s not riskier one way or the other, it’s just nicer if the compiler points it out to you, faster at run time, and there’s less likelihood that the end user will get surprised by an exception. Feedback

For efficiency and type checking, it’s always worth trying to use an array. However, when you’re solving a more general problem, arrays can be too restrictive. After looking at arrays, the rest of this chapter will be devoted to the container classes provided by Java. Feedback

Regardless of what type of array you’re working with, the array identifier is actually a reference to a true object that’s created on the heap. This is the object that holds the references to the other objects, and it can be created either implicitly, as part of the array initialization syntax, or explicitly with a new expression. Part of the array object (in fact, the only field or method you can access) is the read-only length member that tells you how many elements can be stored in that array object. The ‘[]’ syntax is the only other access that you have to the array object. Feedback

The following example shows the various ways that an array can be initialized, and how the array references can be assigned to different array objects. It also shows that arrays of objects and arrays of primitives are almost identical in their use. The only difference is that arrays of objects hold references, but arrays of primitives hold the primitive values directly. Feedback

//: c11:ArraySize.java

// Initialization & re-assignment of arrays.

import com.bruceeckel.simpletest.*;

class Weeble {} // A small mythical creature

public class ArraySize {

private static Test monitor = new Test();

public static void main(String[] args) {

// Arrays of objects:

Weeble[] a; // Local uninitialized variable

Weeble[] b = new Weeble[5]; // Null references

Weeble[] c = new Weeble[4];

for(int i = 0; i < c.length; i++)

if(c[i] == null) // Can test for null reference

c[i] = new Weeble();

// Aggregate initialization:

Weeble[] d = {

new Weeble(), new Weeble(), new Weeble()

};

// Dynamic aggregate initialization:

a = new Weeble[] {

new Weeble(), new Weeble()

};

System.out.println("a.length=" + a.length);

System.out.println("b.length = " + b.length);

// The references inside the array are

// automatically initialized to null:

for(int i = 0; i < b.length; i++)

System.out.println("b[" + i + "]=" + b[i]);

System.out.println("c.length = " + c.length);

System.out.println("d.length = " + d.length);

a = d;

System.out.println("a.length = " + a.length);

// Arrays of primitives:

int[] e; // Null reference

int[] f = new int[5];

int[] g = new int[4];

for(int i = 0; i < g.length; i++)

g[i] = i*i;

int[] h = { 11, 47, 93 };

// Compile error: variable e not initialized:

//!System.out.println("e.length=" + e.length);

System.out.println("f.length = " + f.length);

// The primitives inside the array are

// automatically initialized to zero:

for(int i = 0; i < f.length; i++)

System.out.println("f[" + i + "]=" + f[i]);

System.out.println("g.length = " + g.length);

System.out.println("h.length = " + h.length);

e = h;

System.out.println("e.length = " + e.length);

e = new int[] { 1, 2 };

System.out.println("e.length = " + e.length);

monitor.expect(new String[] {

"a.length=2",

"b.length = 5",

"b[0]=null",

"b[1]=null",

"b[2]=null",

"b[3]=null",

"b[4]=null",

"c.length = 4",

"d.length = 3",

"a.length = 3",

"f.length = 5",

"f[0]=0",

"f[1]=0",

"f[2]=0",

"f[3]=0",

"f[4]=0",

"g.length = 4",

"h.length = 3",

"e.length = 3",

"e.length = 2"

});

}

} ///:~The array a is an uninitialized local variable, and the compiler prevents you from doing anything with this reference until you’ve properly initialized it. The array b is initialized to point to an array of Weeble references, but no actual Weeble objects are ever placed in that array. However, you can still ask what the size of the array is, since b is pointing to a legitimate object. This brings up a slight drawback: You can’t find out how many elements are actually in the array, since length tells you only how many elements can be placed in the array; that is, the size of the array object, not the number of elements it actually holds. However, when an array object is created, its references are automatically initialized to null, so you can see whether a particular array slot has an object in it by checking to see whether it’s null. Similarly, an array of primitives is automatically initialized to zero for numeric types, (char)0 for char, and false for boolean. Feedback

Array c shows the creation of the array object followed by the assignment of Weeble objects to all the slots in the array. Array d shows the “aggregate initialization” syntax that causes the array object to be created (implicitly with new on the heap, just like for array c) and initialized with Weeble objects, all in one statement. Feedback

The next array initialization could be thought of as a “dynamic aggregate initialization.” The aggregate initialization used by d must be used at the point of d’s definition, but with the second syntax you can create and initialize an array object anywhere. For example, suppose hide( ) is a method that takes an array of Weeble objects. You could call it by saying:

hide(d);

but you can also dynamically create the array you want to pass as the argument:

hide(new Weeble[] { new Weeble(), new Weeble() });In many situations this syntax provides a more convenient way to write code. Feedback

The expression:

a = d;

shows how you can take a reference that’s attached to one array object and assign it to another array object, just as you can do with any other type of object reference. Now both a and d are pointing to the same array object on the heap. Feedback

The second part of ArraySize.java shows that primitive arrays work just like object arrays except that primitive arrays hold the primitive values directly. Feedback

Container classes can hold only references to Objects. An array, however, can be created to hold primitives directly, as well as references to Objects. It is possible to use the “wrapper” classes, such as Integer, Double, etc., to place primitive values inside a container, but the wrapper classes for primitives can be awkward to use. In addition, it’s much more efficient to create and access an array of primitives than a container of wrapped primitives. Feedback

Of course, if you’re using a primitive type and you need the flexibility of a container that automatically expands when more space is needed, the array won’t work, and you’re forced to use a container of wrapped primitives. You might think that there should be a specialized type of ArrayList for each of the primitive data types, but Java doesn’t provide this for you.[52] Feedback

Suppose you’re writing a method and you don’t just want to return just one thing, but a whole bunch of things. Languages like C and C++ make this difficult because you can’t just return an array, only a pointer to an array. This introduces problems because it becomes messy to control the lifetime of the array, which easily leads to memory leaks. Feedback

Java takes a similar approach, but you just “return an array.” Unlike C++, with Java you never worry about responsibility for that array—it will be around as long as you need it, and the garbage collector will clean it up when you’re done. Feedback

As an example, consider returning an array of String:

//: c11:IceCream.java

// Returning arrays from methods.

import com.bruceeckel.simpletest.*;

import java.util.*;

public class IceCream {

private static Test monitor = new Test();

private static Random rand = new Random();

public static final String[] flavors = {

"Chocolate", "Strawberry", "Vanilla Fudge Swirl",

"Mint Chip", "Mocha Almond Fudge", "Rum Raisin",

"Praline Cream", "Mud Pie"

};

public static String[] flavorSet(int n) {

String[] results = new String[n];

boolean[] picked = new boolean[flavors.length];

for(int i = 0; i < n; i++) {

int t;

do

t = rand.nextInt(flavors.length);

while(picked[t]);

results[i] = flavors[t];

picked[t] = true;

}

return results;

}

public static void main(String[] args) {

for(int i = 0; i < 20; i++) {

System.out.println(

"flavorSet(" + i + ") = ");

String[] fl = flavorSet(flavors.length);

for(int j = 0; j < fl.length; j++)

System.out.println("\t" + fl[j]);

monitor.expect(new Object[] {

"%% flavorSet\\(\\d+\\) = ",

new TestExpression("%% \\t(Chocolate|Strawberry|"

+ "Vanilla Fudge Swirl|Mint Chip|Mocha Almond "

+ "Fudge|Rum Raisin|Praline Cream|Mud Pie)", 8)

});

}

}

} ///:~The method flavorSet( ) creates an array of String called results. The size of this array is n, determined by the argument that you pass into the method. Then it proceeds to choose flavors randomly from the array flavors and place them into results, which it finally returns. Returning an array is just like returning any other object—it’s a reference. It’s not important that the array was created within flavorSet( ), or that the array was created anyplace else, for that matter. The garbage collector takes care of cleaning up the array when you’re done with it, and the array will persist for as long as you need it. Feedback

As an aside, notice that when flavorSet( ) chooses flavors randomly, it ensures that a particular choice hasn’t already been selected. This is performed in a do loop that keeps making random choices until it finds one not already in the picked array. (Of course, a String comparison also could have been performed to see if the random choice was already in the results array.) If it’s successful, it adds the entry and finds the next one (i gets incremented). Feedback

main( ) prints out 20 full sets of flavors, so you can see that flavorSet( ) chooses the flavors in a random order each time. It’s easiest to see this if you redirect the output into a file. And while you’re looking at the file, remember that you just want the ice cream, you don’t need it. Feedback

In java.util, you’ll find the Arrays class, which holds a set of static methods that perform utility functions for arrays. There are four basic methods: equals( ), to compare two arrays for equality; fill( ), to fill an array with a value; sort( ), to sort the array; and binarySearch( ), to find an element in a sorted array. All of these methods are overloaded for all the primitive types and Objects. In addition, there’s a single asList( ) method that takes any array and turns it into a List container, which you’ll learn about later in this chapter. Feedback

Although useful, the Arrays class stops short of being fully functional. For example, it would be nice to be able to easily print the elements of an array without having to code a for loop by hand every time. And as you’ll see, the fill( ) method only takes a single value and places it in the array, so if you wanted, for example, to fill an array with randomly generated numbers, fill( ) is no help. Feedback

Thus it makes sense to supplement the Arrays class with some additional utilities, which will be placed in the package com.bruceeckel.util for convenience. These will print an array of any type and fill an array with values or objects that are created by an object called a generator that you can define. Feedback

Because code needs to be created for each primitive type as well as Object, there’s a lot of nearly duplicated code.[53] For example, a “generator” interface is required for each type because the return type of next( ) must be different in each case: Feedback

//: com:bruceeckel:util:Generator.java

package com.bruceeckel.util;

public interface Generator { Object next(); } ///:~//: com:bruceeckel:util:BooleanGenerator.java

package com.bruceeckel.util;

public interface BooleanGenerator { boolean next(); } ///:~//: com:bruceeckel:util:ByteGenerator.java

package com.bruceeckel.util;

public interface ByteGenerator { byte next(); } ///:~//: com:bruceeckel:util:CharGenerator.java

package com.bruceeckel.util;

public interface CharGenerator { char next(); } ///:~//: com:bruceeckel:util:ShortGenerator.java

package com.bruceeckel.util;

public interface ShortGenerator { short next(); } ///:~//: com:bruceeckel:util:IntGenerator.java

package com.bruceeckel.util;

public interface IntGenerator { int next(); } ///:~//: com:bruceeckel:util:LongGenerator.java

package com.bruceeckel.util;

public interface LongGenerator { long next(); } ///:~//: com:bruceeckel:util:FloatGenerator.java

package com.bruceeckel.util;

public interface FloatGenerator { float next(); } ///:~//: com:bruceeckel:util:DoubleGenerator.java

package com.bruceeckel.util;

public interface DoubleGenerator { double next(); } ///:~Arrays2 contains a variety of toString( ) methods, overloaded for each type. These methods allow you to easily print an array. The toString( ) code introduces the use of StringBuffer instead of String objects. This is a nod to efficiency; when you’re assembling a string in a method that might be called a lot, it’s wiser to use the more efficient StringBuffer rather than the more convenient String operations. Here, the StringBuffer is created with an initial value, and Strings are appended. Finally, the result is converted to a String as the return value: Feedback

//: com:bruceeckel:util:Arrays2.java

// A supplement to java.util.Arrays, to provide additional

// useful functionality when working with arrays. Allows

// any array to be converted to a String, and to be filled

// via a user-defined "generator" object.

package com.bruceeckel.util;

import java.util.*;

public class Arrays2 {

public static String toString(boolean[] a) {

StringBuffer result = new StringBuffer("[");

for(int i = 0; i < a.length; i++) {

result.append(a[i]);

if(i < a.length - 1)

result.append(", ");

}

result.append("]");

return result.toString();

}

public static String toString(byte[] a) {

StringBuffer result = new StringBuffer("[");

for(int i = 0; i < a.length; i++) {

result.append(a[i]);

if(i < a.length - 1)

result.append(", ");

}

result.append("]");

return result.toString();

}

public static String toString(char[] a) {

StringBuffer result = new StringBuffer("[");

for(int i = 0; i < a.length; i++) {

result.append(a[i]);

if(i < a.length - 1)

result.append(", ");

}

result.append("]");

return result.toString();

}

public static String toString(short[] a) {

StringBuffer result = new StringBuffer("[");

for(int i = 0; i < a.length; i++) {

result.append(a[i]);

if(i < a.length - 1)

result.append(", ");

}

result.append("]");

return result.toString();

}

public static String toString(int[] a) {

StringBuffer result = new StringBuffer("[");

for(int i = 0; i < a.length; i++) {

result.append(a[i]);

if(i < a.length - 1)

result.append(", ");

}

result.append("]");

return result.toString();

}

public static String toString(long[] a) {

StringBuffer result = new StringBuffer("[");

for(int i = 0; i < a.length; i++) {

result.append(a[i]);

if(i < a.length - 1)

result.append(", ");

}

result.append("]");

return result.toString();

}

public static String toString(float[] a) {

StringBuffer result = new StringBuffer("[");

for(int i = 0; i < a.length; i++) {

result.append(a[i]);

if(i < a.length - 1)

result.append(", ");

}

result.append("]");

return result.toString();

}

public static String toString(double[] a) {

StringBuffer result = new StringBuffer("[");

for(int i = 0; i < a.length; i++) {

result.append(a[i]);

if(i < a.length - 1)

result.append(", ");

}

result.append("]");

return result.toString();

}

// Fill an array using a generator:

public static void fill(Object[] a, Generator gen) {

fill(a, 0, a.length, gen);

}

public static void

fill(Object[] a, int from, int to, Generator gen) {

for(int i = from; i < to; i++)

a[i] = gen.next();

}

public static void

fill(boolean[] a, BooleanGenerator gen) {

fill(a, 0, a.length, gen);

}

public static void

fill(boolean[] a, int from, int to,BooleanGenerator gen){

for(int i = from; i < to; i++)

a[i] = gen.next();

}

public static void fill(byte[] a, ByteGenerator gen) {

fill(a, 0, a.length, gen);

}

public static void

fill(byte[] a, int from, int to, ByteGenerator gen) {

for(int i = from; i < to; i++)

a[i] = gen.next();

}

public static void fill(char[] a, CharGenerator gen) {

fill(a, 0, a.length, gen);

}

public static void

fill(char[] a, int from, int to, CharGenerator gen) {

for(int i = from; i < to; i++)

a[i] = gen.next();

}

public static void fill(short[] a, ShortGenerator gen) {

fill(a, 0, a.length, gen);

}

public static void

fill(short[] a, int from, int to, ShortGenerator gen) {

for(int i = from; i < to; i++)

a[i] = gen.next();

}

public static void fill(int[] a, IntGenerator gen) {

fill(a, 0, a.length, gen);

}

public static void

fill(int[] a, int from, int to, IntGenerator gen) {

for(int i = from; i < to; i++)

a[i] = gen.next();

}

public static void fill(long[] a, LongGenerator gen) {

fill(a, 0, a.length, gen);

}

public static void

fill(long[] a, int from, int to, LongGenerator gen) {

for(int i = from; i < to; i++)

a[i] = gen.next();

}

public static void fill(float[] a, FloatGenerator gen) {

fill(a, 0, a.length, gen);

}

public static void

fill(float[] a, int from, int to, FloatGenerator gen) {

for(int i = from; i < to; i++)

a[i] = gen.next();

}

public static void fill(double[] a, DoubleGenerator gen){

fill(a, 0, a.length, gen);

}

public static void

fill(double[] a, int from, int to, DoubleGenerator gen) {

for(int i = from; i < to; i++)

a[i] = gen.next();

}

private static Random r = new Random();

public static class

RandBooleanGenerator implements BooleanGenerator {

public boolean next() { return r.nextBoolean(); }

}

public static class

RandByteGenerator implements ByteGenerator {

public byte next() { return (byte)r.nextInt(); }

}

private static String ssource =

"ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZabcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz";

private static char[] src = ssource.toCharArray();

public static class

RandCharGenerator implements CharGenerator {

public char next() {

return src[r.nextInt(src.length)];

}

}

public static class

RandStringGenerator implements Generator {

private int len;

private RandCharGenerator cg = new RandCharGenerator();

public RandStringGenerator(int length) {

len = length;

}

public Object next() {

char[] buf = new char[len];

for(int i = 0; i < len; i++)

buf[i] = cg.next();

return new String(buf);

}

}

public static class

RandShortGenerator implements ShortGenerator {

public short next() { return (short)r.nextInt(); }

}

public static class

RandIntGenerator implements IntGenerator {

private int mod = 10000;

public RandIntGenerator() {}

public RandIntGenerator(int modulo) { mod = modulo; }

public int next() { return r.nextInt(mod); }

}

public static class

RandLongGenerator implements LongGenerator {

public long next() { return r.nextLong(); }

}

public static class

RandFloatGenerator implements FloatGenerator {

public float next() { return r.nextFloat(); }

}

public static class

RandDoubleGenerator implements DoubleGenerator {

public double next() {return r.nextDouble();}

}

} ///:~To fill an array of elements using a generator, the fill( ) method takes a reference to an appropriate generator interface, which has a next( ) method that will somehow produce an object of the right type (depending on how the interface is implemented). The fill( ) method simply calls next( ) until the desired range has been filled. Now you can create any generator by implementing the appropriate interface and use your generator with fill( ). Feedback

Random data generators are useful for testing, so a set of inner classes is created to implement all the primitive generator interfaces, as well as a String generator to represent Object. You can see that RandStringGenerator uses RandCharGenerator to fill an array of characters, which is then turned into a String. The size of the array is determined by the constructor argument. Feedback

To generate numbers that aren’t too large, RandIntGenerator defaults to a modulus of 10,000, but the overloaded constructor allows you to choose a smaller value. Feedback

Here’s a program to test the library and demonstrate how it is used:

//: c11:TestArrays2.java

// Test and demonstrate Arrays2 utilities.

import com.bruceeckel.util.*;

public class TestArrays2 {

public static void main(String[] args) {

int size = 6;

// Or get the size from the command line:

if(args.length != 0) {

size = Integer.parseInt(args[0]);

if(size < 3) {

System.out.println("arg must be >= 3");

System.exit(1);

}

}

boolean[] a1 = new boolean[size];

byte[] a2 = new byte[size];

char[] a3 = new char[size];

short[] a4 = new short[size];

int[] a5 = new int[size];

long[] a6 = new long[size];

float[] a7 = new float[size];

double[] a8 = new double[size];

Arrays2.fill(a1, new Arrays2.RandBooleanGenerator());

System.out.println("a1 = " + Arrays2.toString(a1));

Arrays2.fill(a2, new Arrays2.RandByteGenerator());

System.out.println("a2 = " + Arrays2.toString(a2));

Arrays2.fill(a3, new Arrays2.RandCharGenerator());

System.out.println("a3 = " + Arrays2.toString(a3));

Arrays2.fill(a4, new Arrays2.RandShortGenerator());

System.out.println("a4 = " + Arrays2.toString(a4));

Arrays2.fill(a5, new Arrays2.RandIntGenerator());

System.out.println("a5 = " + Arrays2.toString(a5));

Arrays2.fill(a6, new Arrays2.RandLongGenerator());

System.out.println("a6 = " + Arrays2.toString(a6));

Arrays2.fill(a7, new Arrays2.RandFloatGenerator());

System.out.println("a7 = " + Arrays2.toString(a7));

Arrays2.fill(a8, new Arrays2.RandDoubleGenerator());

System.out.println("a8 = " + Arrays2.toString(a8));

}

} ///:~The size parameter has a default value, but you can also set it from the command line. Feedback

The Java standard library Arrays also has a fill( ) method, but that is rather trivial; it only duplicates a single value into each location, or in the case of objects, copies the same reference into each location. Using Arrays2.toString( ), the Arrays.fill( ) methods can be easily demonstrated:

//: c11:FillingArrays.java

// Using Arrays.fill()

import com.bruceeckel.simpletest.*;

import com.bruceeckel.util.*;

import java.util.*;

public class FillingArrays {

private static Test monitor = new Test();

public static void main(String[] args) {

int size = 6;

// Or get the size from the command line:

if(args.length != 0)

size = Integer.parseInt(args[0]);

boolean[] a1 = new boolean[size];

byte[] a2 = new byte[size];

char[] a3 = new char[size];

short[] a4 = new short[size];

int[] a5 = new int[size];

long[] a6 = new long[size];

float[] a7 = new float[size];

double[] a8 = new double[size];

String[] a9 = new String[size];

Arrays.fill(a1, true);

System.out.println("a1 = " + Arrays2.toString(a1));

Arrays.fill(a2, (byte)11);

System.out.println("a2 = " + Arrays2.toString(a2));

Arrays.fill(a3, 'x');

System.out.println("a3 = " + Arrays2.toString(a3));

Arrays.fill(a4, (short)17);

System.out.println("a4 = " + Arrays2.toString(a4));

Arrays.fill(a5, 19);

System.out.println("a5 = " + Arrays2.toString(a5));

Arrays.fill(a6, 23);

System.out.println("a6 = " + Arrays2.toString(a6));

Arrays.fill(a7, 29);

System.out.println("a7 = " + Arrays2.toString(a7));

Arrays.fill(a8, 47);

System.out.println("a8 = " + Arrays2.toString(a8));

Arrays.fill(a9, "Hello");

System.out.println("a9 = " + Arrays.asList(a9));

// Manipulating ranges:

Arrays.fill(a9, 3, 5, "World");

System.out.println("a9 = " + Arrays.asList(a9));

monitor.expect(new String[] {

"a1 = [true, true, true, true, true, true]",

"a2 = [11, 11, 11, 11, 11, 11]",

"a3 = [x, x, x, x, x, x]",

"a4 = [17, 17, 17, 17, 17, 17]",

"a5 = [19, 19, 19, 19, 19, 19]",

"a6 = [23, 23, 23, 23, 23, 23]",

"a7 = [29.0, 29.0, 29.0, 29.0, 29.0, 29.0]",

"a8 = [47.0, 47.0, 47.0, 47.0, 47.0, 47.0]",

"a9 = [Hello, Hello, Hello, Hello, Hello, Hello]",

"a9 = [Hello, Hello, Hello, World, World, Hello]"

});

}

} ///:~You can either fill the entire array or, as the last two statements show, a range of elements. But since you can only provide a single value to use for filling using Arrays.fill( ), the Arrays2.fill( ) methods produce much more interesting results. Feedback

The Java standard library provides a static method, System.arraycopy( ), which can make much faster copies of an array than if you use a for loop to perform the copy by hand. System.arraycopy( ) is overloaded to handle all types. Here’s an example that manipulates arrays of int:

//: c11:CopyingArrays.java

// Using System.arraycopy()

import com.bruceeckel.simpletest.*;

import com.bruceeckel.util.*;

import java.util.*;

public class CopyingArrays {

private static Test monitor = new Test();

public static void main(String[] args) {

int[] i = new int[7];

int[] j = new int[10];

Arrays.fill(i, 47);

Arrays.fill(j, 99);

System.out.println("i = " + Arrays2.toString(i));

System.out.println("j = " + Arrays2.toString(j));

System.arraycopy(i, 0, j, 0, i.length);

System.out.println("j = " + Arrays2.toString(j));

int[] k = new int[5];

Arrays.fill(k, 103);

System.arraycopy(i, 0, k, 0, k.length);

System.out.println("k = " + Arrays2.toString(k));

Arrays.fill(k, 103);

System.arraycopy(k, 0, i, 0, k.length);

System.out.println("i = " + Arrays2.toString(i));

// Objects:

Integer[] u = new Integer[10];

Integer[] v = new Integer[5];

Arrays.fill(u, new Integer(47));

Arrays.fill(v, new Integer(99));

System.out.println("u = " + Arrays.asList(u));

System.out.println("v = " + Arrays.asList(v));

System.arraycopy(v, 0, u, u.length/2, v.length);

System.out.println("u = " + Arrays.asList(u));

monitor.expect(new String[] {

"i = [47, 47, 47, 47, 47, 47, 47]",

"j = [99, 99, 99, 99, 99, 99, 99, 99, 99, 99]",

"j = [47, 47, 47, 47, 47, 47, 47, 99, 99, 99]",

"k = [47, 47, 47, 47, 47]",

"i = [103, 103, 103, 103, 103, 47, 47]",

"u = [47, 47, 47, 47, 47, 47, 47, 47, 47, 47]",

"v = [99, 99, 99, 99, 99]",

"u = [47, 47, 47, 47, 47, 99, 99, 99, 99, 99]"

});

}

} ///:~The arguments to arraycopy( ) are the source array, the offset into the source array from whence to start copying, the destination array, the offset into the destination array where the copying begins, and the number of elements to copy. Naturally, any violation of the array boundaries will cause an exception. Feedback

The example shows that both primitive arrays and object arrays can be copied. However, if you copy arrays of objects, then only the references get copied—there’s no duplication of the objects themselves. This is called a shallow copy (see Appendix A). Feedback

Arrays provides the overloaded method equals( ) to compare entire arrays for equality. Again, these are overloaded for all the primitives and for Object. To be equal, the arrays must have the same number of elements, and each element must be equivalent to each corresponding element in the other array, using the equals( ) for each element. (For primitives, that primitive’s wrapper class equals( ) is used; for example, Integer.equals( ) for int.) For example:

//: c11:ComparingArrays.java

// Using Arrays.equals()

import com.bruceeckel.simpletest.*;

import java.util.*;

public class ComparingArrays {

private static Test monitor = new Test();

public static void main(String[] args) {

int[] a1 = new int[10];

int[] a2 = new int[10];

Arrays.fill(a1, 47);

Arrays.fill(a2, 47);

System.out.println(Arrays.equals(a1, a2));

a2[3] = 11;

System.out.println(Arrays.equals(a1, a2));

String[] s1 = new String[5];

Arrays.fill(s1, "Hi");

String[] s2 = {"Hi", "Hi", "Hi", "Hi", "Hi"};

System.out.println(Arrays.equals(s1, s2));

monitor.expect(new String[] {

"true",

"false",

"true"

});

}

} ///:~Originally, a1 and a2 are exactly equal, so the output is “true,” but then one of the elements is changed, which makes the result “false.” In the last case, all the elements of s1 point to the same object, but s2 has five unique objects. However, array equality is based on contents (via Object.equals( )) , so the result is “true.” Feedback

One of the missing features in the Java 1.0 and 1.1 libraries was algorithmic operations—even simple sorting. This was a rather confusing situation to someone expecting an adequate standard library. Fortunately, Java 2 remedied the situation, at least for the sorting problem. Feedback

A problem with writing generic sorting code is that sorting must perform comparisons based on the actual type of the object. Of course, one approach is to write a different sorting method for every different type, but you should be able to recognize that this does not produce code that is easily reused for new types. Feedback

A primary goal of programming design is to “separate things that change from things that stay the same,” and here, the code that stays the same is the general sort algorithm, but the thing that changes from one use to the next is the way objects are compared. So instead of placing the comparison code into many different sort routines, the technique of the callback is used. With a callback, the part of the code that varies from case to case is separated, and the part of the code that’s always the same will call back to the code that changes. Feedback

Java has two ways to provide comparison functionality. The first is with the “natural” comparison method that is imparted to a class by implementing the java.lang.Comparable interface. This is a very simple interface with a single method, compareTo( ). This method takes another Object as an argument and produces a negative value if the current object is less than the argument, zero if the argument is equal, and a positive value if the current object is greater than the argument . Feedback

Here’s a class that implements Comparable and demonstrates the comparability by using the Java standard library method Arrays.sort( ):

//: c11:CompType.java

// Implementing Comparable in a class.

import com.bruceeckel.util.*;

import java.util.*;

public class CompType implements Comparable {

int i;

int j;

public CompType(int n1, int n2) {

i = n1;

j = n2;

}

public String toString() {

return "[i = " + i + ", j = " + j + "]";

}

public int compareTo(Object rv) {

int rvi = ((CompType)rv).i;

return (i < rvi ? -1 : (i == rvi ? 0 : 1));

}

private static Random r = new Random();

public static Generator generator() {

return new Generator() {

public Object next() {

return new CompType(r.nextInt(100),r.nextInt(100));

}

};

}

public static void main(String[] args) {

CompType[] a = new CompType[10];

Arrays2.fill(a, generator());

System.out.println(

"before sorting, a = " + Arrays.asList(a));

Arrays.sort(a);

System.out.println(

"after sorting, a = " + Arrays.asList(a));

}

} ///:~When you define the comparison method, you are responsible for deciding what it means to compare one of your objects to another. Here, only the i values are used in the comparison, and the j values are ignored. Feedback

The static randInt( ) method produces positive values between zero and 100, and the generator( ) method produces an object that implements the Generator interface by creating an anonymous inner class (see Chapter 8). This builds CompType objects by initializing them with random values. In main( ), the generator is used to fill an array of CompType, which is then sorted. If Comparable hadn’t been implemented, then you’d get a ClassCastException at run time when you tried to call sort( ). This is because sort( ) casts its argument to Comparable. Feedback

Now suppose someone hands you a class that doesn’t implement Comparable, or hands you this class that does implement Comparable, but you decide you don’t like the way it works and would rather have a different comparison method for the type. The solution is in contrast to hard-wiring the comparison code into each different object. Instead, the strategy design pattern[54] is used. With a strategy, the part of the code that varies is encapsulated inside its own class (the strategy object). You hand a strategy object to the code that’s always the same, which uses the strategy to fulfill its algorithm. That way, you can make different objects to express different ways of comparison and feed them to the same sorting code. Here, you create a strategy by defining a separate class that implements an interface called Comparator. This has two methods, compare( ) and equals( ). However, you don’t have to implement equals( ) except for special performance needs, because anytime you create a class, it is implicitly inherited from Object, which has an equals( ). So you can just use the default Object equals( ) and satisfy the contract imposed by the interface. Feedback

The Collections class (which we’ll look at more later) contains a single Comparator that reverses the natural sorting order. This can be applied easily to the CompType: Feedback

//: c11:Reverse.java

// The Collecions.reverseOrder() Comparator

import com.bruceeckel.util.*;

import java.util.*;

public class Reverse {

public static void main(String[] args) {

CompType[] a = new CompType[10];

Arrays2.fill(a, CompType.generator());

System.out.println(

"before sorting, a = " + Arrays.asList(a));

Arrays.sort(a, Collections.reverseOrder());

System.out.println(

"after sorting, a = " + Arrays.asList(a));

}

} ///:~The call to Collections.reverseOrder( ) produces the reference to the Comparator. Feedback

As a second example, the following Comparator compares CompType objects based on their j values rather than their i values:

//: c11:ComparatorTest.java

// Implementing a Comparator for a class.

import com.bruceeckel.util.*;

import java.util.*;

class CompTypeComparator implements Comparator {

public int compare(Object o1, Object o2) {

int j1 = ((CompType)o1).j;

int j2 = ((CompType)o2).j;

return (j1 < j2 ? -1 : (j1 == j2 ? 0 : 1));

}

}

public class ComparatorTest {

public static void main(String[] args) {

CompType[] a = new CompType[10];

Arrays2.fill(a, CompType.generator());

System.out.println(

"before sorting, a = " + Arrays.asList(a));

Arrays.sort(a, new CompTypeComparator());

System.out.println(

"after sorting, a = " + Arrays.asList(a));

}

} ///:~The compare( ) method must return a negative integer, zero, or positive integer if the first argument is less than, equal to, or greater than the second, respectively. Feedback

With the built-in sorting methods, you can sort any array of primitives, or any array of objects that either implements Comparable or has an associated Comparator. This fills a big hole in the Java libraries; believe it or not, there was no support in Java 1.0 or 1.1 for sorting Strings! Here’s an example that generates random String objects and sorts them:

//: c11:StringSorting.java

// Sorting an array of Strings.

import com.bruceeckel.util.*;

import java.util.*;

public class StringSorting {

public static void main(String[] args) {

String[] sa = new String[30];

Arrays2.fill(sa, new Arrays2.RandStringGenerator(5));

System.out.println(

"Before sorting: " + Arrays.asList(sa));

Arrays.sort(sa);

System.out.println(

"After sorting: " + Arrays.asList(sa));

}

} ///:~One thing you’ll notice about the output in the String sorting algorithm is that it’s lexicographic, so it puts all the words starting with uppercase letters first, followed by all the words starting with lowercase letters. (Telephone books are typically sorted this way.) You may also want to group the words together regardless of case, and you can do this by defining a Comparator class, thereby overriding the default String Comparable behavior. For reuse, this will be added to the “util” package: Feedback

//: com:bruceeckel:util:AlphabeticComparator.java

// Keeping upper and lowercase letters together.

package com.bruceeckel.util;

import java.util.*;

public class AlphabeticComparator implements Comparator {

public int compare(Object o1, Object o2) {

String s1 = (String)o1;

String s2 = (String)o2;

return s1.toLowerCase().compareTo(s2.toLowerCase());

}

} ///:~By casting to String at the beginning, you’ll get an exception if you attempt to use this with the wrong type. Each String is converted to lowercase before the comparison. String’s built-in compareTo( ) method provides the desired functionality. Feedback

Here’s a test using AlphabeticComparator:

//: c11:AlphabeticSorting.java

// Keeping upper and lowercase letters together.

import com.bruceeckel.util.*;

import java.util.*;

public class AlphabeticSorting {

public static void main(String[] args) {

String[] sa = new String[30];

Arrays2.fill(sa, new Arrays2.RandStringGenerator(5));

System.out.println(

"Before sorting: " + Arrays.asList(sa));

Arrays.sort(sa, new AlphabeticComparator());

System.out.println(

"After sorting: " + Arrays.asList(sa));

}

} ///:~The sorting algorithm that’s used in the Java standard library is designed to be optimal for the particular type you’re sorting—a Quicksort for primitives, and a stable merge sort for objects. So you shouldn’t need to spend any time worrying about performance unless your profiler points you to the sorting process as a bottleneck. Feedback

Once an array is sorted, you can perform a fast search for a particular item by using Arrays.binarySearch( ). However, it’s very important that you do not try to use binarySearch( ) on an unsorted array; the results will be unpredictable. The following example uses a RandIntGenerator to fill an array, and then uses the same generator to produce values to search for: Feedback

//: c11:ArraySearching.java

// Using Arrays.binarySearch().

import com.bruceeckel.util.*;

import java.util.*;

public class ArraySearching {

public static void main(String[] args) {

int[] a = new int[100];

Arrays2.RandIntGenerator gen =

new Arrays2.RandIntGenerator(1000);

Arrays2.fill(a, gen);

Arrays.sort(a);

System.out.println(

"Sorted array: " + Arrays2.toString(a));

while(true) {

int r = gen.next();

int location = Arrays.binarySearch(a, r);

if(location >= 0) {

System.out.println("Location of " + r +

" is " + location + ", a[" +

location + "] = " + a[location]);

break; // Out of while loop

}

}

}

} ///:~In the while loop, random values are generated as search items until one of them is found. Feedback

Arrays.binarySearch( ) produces a value greater than or equal to zero if the search item is found. Otherwise, it produces a negative value representing the place that the element should be inserted if you are maintaining the sorted array by hand. The value produced is

-(insertion point) - 1

The insertion point is the index of the first element greater than the key, or a.size( ), if all elements in the array are less than the specified key. Feedback

If the array contains duplicate elements, there is no guarantee which one will be found. The algorithm is thus not really designed to support duplicate elements, but rather to tolerate them. If you need a sorted list of nonduplicated elements, use a TreeSet (to maintain sorted order) or LinkedHashSet (to maintain insertion order), which will be introduced later in this chapter. These classes take care of all the details for you automatically. Only in cases of performance bottlenecks should you replace one of these classes with a hand-maintained array. Feedback

If you have sorted an object array using a Comparator (primitive arrays do not allow sorting with a Comparator), you must include that same Comparator when you perform a binarySearch( ) (using the overloaded version of the method that’s provided). For example, the AlphabeticSorting.java program can be modified to perform a search:

//: c11:AlphabeticSearch.java

// Searching with a Comparator.

import com.bruceeckel.simpletest.*;

import com.bruceeckel.util.*;

import java.util.*;

public class AlphabeticSearch {

private static Test monitor = new Test();

public static void main(String[] args) {

String[] sa = new String[30];

Arrays2.fill(sa, new Arrays2.RandStringGenerator(5));

AlphabeticComparator comp = new AlphabeticComparator();

Arrays.sort(sa, comp);

int index = Arrays.binarySearch(sa, sa[10], comp);

System.out.println("Index = " + index);

monitor.expect(new String[] {

"Index = 10"

});

}

} ///:~The Comparator must be passed to the overloaded binarySearch( ) as the third argument. In this example, success is guaranteed because the search item is selected from the array itself. Feedback

To summarize what you’ve seen so far, your first and most efficient choice to hold a group of objects should be an array, and you’re forced into this choice if you want to hold a group of primitives. In the remainder of this chapter we’ll look at the more general case, when you don’t know at the time you’re writing the program how many objects you’re going to need, or if you need a more sophisticated way to store your objects. Java provides a library of container classes to solve this problem, the basic types of which are List, Set, and Map. You can solve a surprising number of problems by using these tools. Feedback

Among their other characteristics—Set, for example, holds only one object of each value, and Map is an associative array that lets you associate any object with any other object—the Java container classes will automatically resize themselves. So, unlike arrays, you can put in any number of objects and you don’t need to worry about how big to make the container while you’re writing the program. Feedback

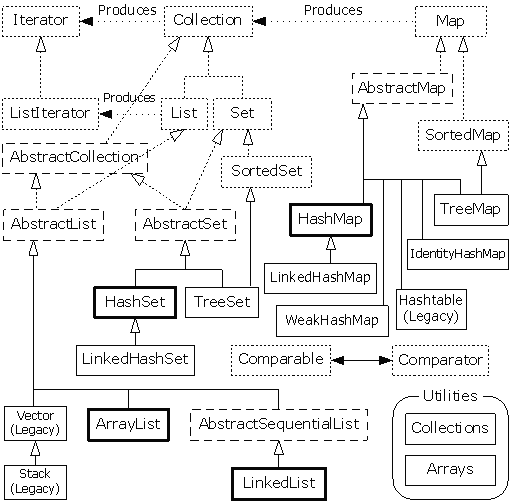

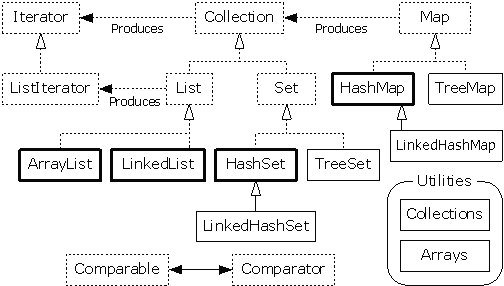

To me, container classes are one of the most powerful tools for raw development because they significantly increase your programming muscle. The Java 2 containers represent a thorough redesign[55] of the rather poor showings in Java 1.0 and 1.1. Some of the redesign makes things tighter and more sensible. It also fills out the functionality of the containers library, providing the behavior of linked lists, queues, and deques (double-ended queues, pronounced “decks”). Feedback

The design of a containers library is difficult (true of most library design problems). In C++, the container classes covered the bases with many different classes. This was better than what was available prior to the C++ container classes (nothing), but it didn’t translate well into Java. At the other extreme, I’ve seen a containers library that consists of a single class, “container,” which acts like both a linear sequence and an associative array at the same time. The Java 2 container library strikes a balance: the full functionality that you expect from a mature container library, but easier to learn and use than the C++ container classes and other similar container libraries. The result can seem a bit odd in places. Unlike some of the decisions made in the early Java libraries, these oddities were not accidents, but carefully considered decisions based on trade-offs in complexity. It might take you a little while to get comfortable with some aspects of the library, but I think you’ll find yourself rapidly acquiring and using these new tools. Feedback

The Java 2 container library takes the issue of “holding your objects” and divides it into two distinct concepts:

We will first look at the general features of containers, then go into details, and finally learn why there are different versions of some containers and how to choose between them. Feedback

Unlike arrays, the containers print nicely without any help. Here’s an example that also introduces you to the basic types of containers:

//: c11:PrintingContainers.java

// Containers print themselves automatically.

import com.bruceeckel.simpletest.*;

import java.util.*;

public class PrintingContainers {

private static Test monitor = new Test();

static Collection fill(Collection c) {

c.add("dog");

c.add("dog");

c.add("cat");

return c;

}

static Map fill(Map m) {

m.put("dog", "Bosco");

m.put("dog", "Spot");

m.put("cat", "Rags");

return m;

}

public static void main(String[] args) {

System.out.println(fill(new ArrayList()));

System.out.println(fill(new HashSet()));

System.out.println(fill(new HashMap()));

monitor.expect(new String[] {

"[dog, dog, cat]",

"[dog, cat]",

"{dog=Spot, cat=Rags}"

});

}

} ///:~As mentioned before, there are two basic categories in the Java container library. The distinction is based on the number of items that are held in each location of the container. The Collection category only holds one item in each location (the name is a bit misleading, because entire container libraries are often called “collections”). It includes the List, which holds a group of items in a specified sequence, and the Set, which only allows the addition of one item of each type. The ArrayList is a type of List, and HashSet is a type of Set. To add items to any Collection, there’s an add( ) method. Feedback

The Map holds key-value pairs, rather like a mini database. The preceding example uses one flavor of Map, the HashMap. If you have a Map that associates states with their capitals and you want to know the capital of Ohio, you look it up—almost as if you were indexing into an array. (Maps are also called associative arrays.) To add elements to a Map, there’s a put( ) method that takes a key and a value as arguments. The example only shows adding elements and does not look up the elements after they’re added. That will be shown later. Feedback

The overloaded fill( ) methods fill Collections and Maps, respectively. If you look at the output, you can see that the default printing behavior (provided via the container’s various toString( ) methods) produces quite readable results, so no additional printing support is necessary as it was with arrays. A Collection is printed surrounded by square brackets, with each element separated by a comma. A Map is surrounded by curly braces, with each key and value associated with an equal sign (keys on the left, values on the right). Feedback

You can also immediately see the basic behavior of the different containers. The List holds the objects exactly as they are entered, without any reordering or editing. The Set, however, only accepts one of each object, and it uses its own internal ordering method (in general, you are only concerned with whether or not something is a member of the Set, not the order in which it appears—for that you’d use a List). And the Map also only accepts one of each type of item, based on the key, and it also has its own internal ordering and does not care about the order in which you enter the items. If maintaining the insertion sequence is important, you can use a LinkedHashSet or LinkedHashMap. Feedback

Although the problem of printing the containers is taken care of, filling containers suffers from the same deficiency as java.util.Arrays. Just like Arrays, there is a companion class called Collections containing static utility methods, including one called fill( ). This fill( ) also just duplicates a single object reference throughout the container, and also only works for List objects and not Sets or Maps:

//: c11:FillingLists.java

// The Collections.fill() method.

import com.bruceeckel.simpletest.*;

import java.util.*;

public class FillingLists {

private static Test monitor = new Test();

public static void main(String[] args) {

List list = new ArrayList();

for(int i = 0; i < 10; i++)

list.add("");

Collections.fill(list, "Hello");

System.out.println(list);

monitor.expect(new String[] {

"[Hello, Hello, Hello, Hello, Hello, " +

"Hello, Hello, Hello, Hello, Hello]"

});

}

} ///:~This method is made even less useful by the fact that it can only replace elements that are already in the List and will not add new elements. Feedback

To be able to create interesting examples, here is a complementary Collections2 library (part of com.bruceeckel.util for convenience) with a fill( ) method that uses a generator to add elements and allows you to specify the number of elements you want to add( ). The Generator interface defined previously will work for Collections, but the Map requires its own generator interface since a pair of objects (one key and one value) must be produced by each call to next( ). Here is the Pair class:

//: com:bruceeckel:util:Pair.java

package com.bruceeckel.util;

public class Pair {

public Object key, value;

public Pair(Object k, Object v) {

key = k;

value = v;

}

} ///:~Next, the generator interface that produces the Pair:

//: com:bruceeckel:util:MapGenerator.java

package com.bruceeckel.util;

public interface MapGenerator { Pair next(); } ///:~With these, a set of utilities for working with the container classes can be developed:

//: com:bruceeckel:util:Collections2.java

// To fill any type of container using a generator object.

package com.bruceeckel.util;

import java.util.*;

public class Collections2 {

// Fill an array using a generator:

public static void

fill(Collection c, Generator gen, int count) {

for(int i = 0; i < count; i++)

c.add(gen.next());

}

public static void

fill(Map m, MapGenerator gen, int count) {

for(int i = 0; i < count; i++) {

Pair p = gen.next();

m.put(p.key, p.value);

}

}

public static class

RandStringPairGenerator implements MapGenerator {

private Arrays2.RandStringGenerator gen;

public RandStringPairGenerator(int len) {

gen = new Arrays2.RandStringGenerator(len);

}

public Pair next() {

return new Pair(gen.next(), gen.next());

}

}

// Default object so you don't have to create your own:

public static RandStringPairGenerator rsp =

new RandStringPairGenerator(10);

public static class

StringPairGenerator implements MapGenerator {

private int index = -1;

private String[][] d;

public StringPairGenerator(String[][] data) {

d = data;

}

public Pair next() {

// Force the index to wrap:

index = (index + 1) % d.length;

return new Pair(d[index][0], d[index][1]);

}

public StringPairGenerator reset() {

index = -1;

return this;

}

}

// Use a predefined dataset:

public static StringPairGenerator geography =

new StringPairGenerator(CountryCapitals.pairs);

// Produce a sequence from a 2D array:

public static class StringGenerator implements Generator{

private String[][] d;

private int position;

private int index = -1;

public StringGenerator(String[][] data, int pos) {

d = data;

position = pos;

}

public Object next() {

// Force the index to wrap:

index = (index + 1) % d.length;

return d[index][position];

}

public StringGenerator reset() {

index = -1;

return this;

}

}

// Use a predefined dataset:

public static StringGenerator countries =

new StringGenerator(CountryCapitals.pairs, 0);

public static StringGenerator capitals =

new StringGenerator(CountryCapitals.pairs, 1);

} ///:~Both versions of fill( ) take an argument that determines the number of items to add to the container. In addition, there are two generators for the map: RandStringPairGenerator, which creates any number of pairs of gibberish Strings with length determined by the constructor argument; and StringPairGenerator, which produces pairs of Strings given a two-dimensional array of String. The StringGenerator also takes a two-dimensional array of String but generates single items rather than Pairs. The static rsp, geography, countries, and capitals objects provide prebuilt generators, the last three using all the countries of the world and their capitals. Note that if you try to create more pairs than are available, the generators will loop around to the beginning, and if you are putting the pairs into a Map, the duplicates will just be ignored. Feedback

Here is the predefined dataset, which consists of country names and their capitals:

//: com:bruceeckel:util:CountryCapitals.java

package com.bruceeckel.util;

public class CountryCapitals {

public static final String[][] pairs = {

// Africa

{"ALGERIA","Algiers"}, {"ANGOLA","Luanda"},

{"BENIN","Porto-Novo"}, {"BOTSWANA","Gaberone"},

{"BURKINA FASO","Ouagadougou"},

{"BURUNDI","Bujumbura"},

{"CAMEROON","Yaounde"}, {"CAPE VERDE","Praia"},

{"CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC","Bangui"},

{"CHAD","N'djamena"}, {"COMOROS","Moroni"},

{"CONGO","Brazzaville"}, {"DJIBOUTI","Dijibouti"},

{"EGYPT","Cairo"}, {"EQUATORIAL GUINEA","Malabo"},

{"ERITREA","Asmara"}, {"ETHIOPIA","Addis Ababa"},

{"GABON","Libreville"}, {"THE GAMBIA","Banjul"},

{"GHANA","Accra"}, {"GUINEA","Conakry"},

{"GUINEA","-"}, {"BISSAU","Bissau"},

{"COTE D'IVOIR (IVORY COAST)","Yamoussoukro"},

{"KENYA","Nairobi"}, {"LESOTHO","Maseru"},

{"LIBERIA","Monrovia"}, {"LIBYA","Tripoli"},

{"MADAGASCAR","Antananarivo"}, {"MALAWI","Lilongwe"},

{"MALI","Bamako"}, {"MAURITANIA","Nouakchott"},

{"MAURITIUS","Port Louis"}, {"MOROCCO","Rabat"},

{"MOZAMBIQUE","Maputo"}, {"NAMIBIA","Windhoek"},

{"NIGER","Niamey"}, {"NIGERIA","Abuja"},

{"RWANDA","Kigali"},

{"SAO TOME E PRINCIPE","Sao Tome"},

{"SENEGAL","Dakar"}, {"SEYCHELLES","Victoria"},

{"SIERRA LEONE","Freetown"}, {"SOMALIA","Mogadishu"},

{"SOUTH AFRICA","Pretoria/Cape Town"},

{"SUDAN","Khartoum"},

{"SWAZILAND","Mbabane"}, {"TANZANIA","Dodoma"},

{"TOGO","Lome"}, {"TUNISIA","Tunis"},

{"UGANDA","Kampala"},

{"DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO (ZAIRE)",

"Kinshasa"},

{"ZAMBIA","Lusaka"}, {"ZIMBABWE","Harare"},

// Asia

{"AFGHANISTAN","Kabul"}, {"BAHRAIN","Manama"},

{"BANGLADESH","Dhaka"}, {"BHUTAN","Thimphu"},

{"BRUNEI","Bandar Seri Begawan"},

{"CAMBODIA","Phnom Penh"},

{"CHINA","Beijing"}, {"CYPRUS","Nicosia"},

{"INDIA","New Delhi"}, {"INDONESIA","Jakarta"},

{"IRAN","Tehran"}, {"IRAQ","Baghdad"},

{"ISRAEL","Tel Aviv"}, {"JAPAN","Tokyo"},

{"JORDAN","Amman"}, {"KUWAIT","Kuwait City"},

{"LAOS","Vientiane"}, {"LEBANON","Beirut"},

{"MALAYSIA","Kuala Lumpur"}, {"THE MALDIVES","Male"},

{"MONGOLIA","Ulan Bator"},

{"MYANMAR (BURMA)","Rangoon"},

{"NEPAL","Katmandu"}, {"NORTH KOREA","P'yongyang"},

{"OMAN","Muscat"}, {"PAKISTAN","Islamabad"},

{"PHILIPPINES","Manila"}, {"QATAR","Doha"},

{"SAUDI ARABIA","Riyadh"}, {"SINGAPORE","Singapore"},

{"SOUTH KOREA","Seoul"}, {"SRI LANKA","Colombo"},

{"SYRIA","Damascus"},

{"TAIWAN (REPUBLIC OF CHINA)","Taipei"},

{"THAILAND","Bangkok"}, {"TURKEY","Ankara"},

{"UNITED ARAB EMIRATES","Abu Dhabi"},

{"VIETNAM","Hanoi"}, {"YEMEN","Sana'a"},

// Australia and Oceania

{"AUSTRALIA","Canberra"}, {"FIJI","Suva"},

{"KIRIBATI","Bairiki"},

{"MARSHALL ISLANDS","Dalap-Uliga-Darrit"},

{"MICRONESIA","Palikir"}, {"NAURU","Yaren"},

{"NEW ZEALAND","Wellington"}, {"PALAU","Koror"},

{"PAPUA NEW GUINEA","Port Moresby"},

{"SOLOMON ISLANDS","Honaira"}, {"TONGA","Nuku'alofa"},

{"TUVALU","Fongafale"}, {"VANUATU","< Port-Vila"},

{"WESTERN SAMOA","Apia"},

// Eastern Europe and former USSR

{"ARMENIA","Yerevan"}, {"AZERBAIJAN","Baku"},

{"BELARUS (BYELORUSSIA)","Minsk"},

{"GEORGIA","Tbilisi"},

{"KAZAKSTAN","Almaty"}, {"KYRGYZSTAN","Alma-Ata"},

{"MOLDOVA","Chisinau"}, {"RUSSIA","Moscow"},

{"TAJIKISTAN","Dushanbe"}, {"TURKMENISTAN","Ashkabad"},

{"UKRAINE","Kyiv"}, {"UZBEKISTAN","Tashkent"},

// Europe

{"ALBANIA","Tirana"}, {"ANDORRA","Andorra la Vella"},

{"AUSTRIA","Vienna"}, {"BELGIUM","Brussels"},

{"BOSNIA","-"}, {"HERZEGOVINA","Sarajevo"},

{"CROATIA","Zagreb"}, {"CZECH REPUBLIC","Prague"},

{"DENMARK","Copenhagen"}, {"ESTONIA","Tallinn"},

{"FINLAND","Helsinki"}, {"FRANCE","Paris"},

{"GERMANY","Berlin"}, {"GREECE","Athens"},

{"HUNGARY","Budapest"}, {"ICELAND","Reykjavik"},

{"IRELAND","Dublin"}, {"ITALY","Rome"},

{"LATVIA","Riga"}, {"LIECHTENSTEIN","Vaduz"},

{"LITHUANIA","Vilnius"}, {"LUXEMBOURG","Luxembourg"},

{"MACEDONIA","Skopje"}, {"MALTA","Valletta"},

{"MONACO","Monaco"}, {"MONTENEGRO","Podgorica"},

{"THE NETHERLANDS","Amsterdam"}, {"NORWAY","Oslo"},

{"POLAND","Warsaw"}, {"PORTUGAL","Lisbon"},

{"ROMANIA","Bucharest"}, {"SAN MARINO","San Marino"},

{"SERBIA","Belgrade"}, {"SLOVAKIA","Bratislava"},

{"SLOVENIA","Ljujiana"}, {"SPAIN","Madrid"},

{"SWEDEN","Stockholm"}, {"SWITZERLAND","Berne"},

{"UNITED KINGDOM","London"}, {"VATICAN CITY","---"},

// North and Central America

{"ANTIGUA AND BARBUDA","Saint John's"},

{"BAHAMAS","Nassau"},

{"BARBADOS","Bridgetown"}, {"BELIZE","Belmopan"},

{"CANADA","Ottawa"}, {"COSTA RICA","San Jose"},

{"CUBA","Havana"}, {"DOMINICA","Roseau"},

{"DOMINICAN REPUBLIC","Santo Domingo"},

{"EL SALVADOR","San Salvador"},

{"GRENADA","Saint George's"},

{"GUATEMALA","Guatemala City"},

{"HAITI","Port-au-Prince"},

{"HONDURAS","Tegucigalpa"}, {"JAMAICA","Kingston"},

{"MEXICO","Mexico City"}, {"NICARAGUA","Managua"},

{"PANAMA","Panama City"}, {"ST. KITTS","-"},

{"NEVIS","Basseterre"}, {"ST. LUCIA","Castries"},

{"ST. VINCENT AND THE GRENADINES","Kingstown"},

{"UNITED STATES OF AMERICA","Washington, D.C."},

// South America

{"ARGENTINA","Buenos Aires"},

{"BOLIVIA","Sucre (legal)/La Paz(administrative)"},

{"BRAZIL","Brasilia"}, {"CHILE","Santiago"},

{"COLOMBIA","Bogota"}, {"ECUADOR","Quito"},

{"GUYANA","Georgetown"}, {"PARAGUAY","Asuncion"},

{"PERU","Lima"}, {"SURINAME","Paramaribo"},

{"TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO","Port of Spain"},

{"URUGUAY","Montevideo"}, {"VENEZUELA","Caracas"},

};

} ///:~This is simply a two-dimensional array of String data.[56] Here’s a simple test using the fill( ) methods and generators:

//: c11:FillTest.java

import com.bruceeckel.util.*;

import java.util.*;

public class FillTest {

private static Generator sg =

new Arrays2.RandStringGenerator(7);

public static void main(String[] args) {

List list = new ArrayList();

Collections2.fill(list, sg, 25);

System.out.println(list + "\n");

List list2 = new ArrayList();

Collections2.fill(list2, Collections2.capitals, 25);

System.out.println(list2 + "\n");

Set set = new HashSet();

Collections2.fill(set, sg, 25);

System.out.println(set + "\n");

Map m = new HashMap();

Collections2.fill(m, Collections2.rsp, 25);

System.out.println(m + "\n");

Map m2 = new HashMap();

Collections2.fill(m2, Collections2.geography, 25);

System.out.println(m2);

}

} ///:~With these tools you can easily test the various containers by filling them with interesting data. Feedback

The “disadvantage” to using the Java containers is that you lose type information when you put an object into a container. This happens because the programmer of that container class had no idea what specific type you wanted to put in the container, and making the container hold only your type would prevent it from being a general-purpose tool. So instead, the container holds references to Object, which is the root of all the classes, so it holds any type. (Of course, this doesn’t include primitive types, since they aren’t real objects, and thus, are not inherited from anything.) This is a great solution, except: Feedback

On the up side, Java won’t let you misuse the objects that you put into a container. If you throw a dog into a container of cats and then try to treat everything in the container as a cat, you’ll get a RuntimeException when you pull the dog reference out of the cat container and try to cast it to a cat. Feedback

Here’s an example using the basic workhorse container, ArrayList. For starters, you can think of ArrayList as “an array that automatically expands itself.” Using an ArrayList is straightforward: create one, put objects in using add( ), and later get them out with get( ) using an index—just like you would with an array, but without the square brackets.[57] ArrayList also has a method size( ) to let you know how many elements have been added so you don’t inadvertently run off the end and cause an exception. Feedback

First, Cat and Dog classes are created:

//: c11:Cat.java

package c11;

public class Cat {

private int catNumber;

public Cat(int i) { catNumber = i; }

public void id() {

System.out.println("Cat #" + catNumber);

}

} ///:~//: c11:Dog.java

package c11;

public class Dog {

private int dogNumber;

public Dog(int i) { dogNumber = i; }

public void id() {

System.out.println("Dog #" + dogNumber);

}

} ///:~Cats and Dogs are placed into the container, then pulled out:

//: c11:CatsAndDogs.java

// Simple container example.

// {ThrowsException}

package c11;

import java.util.*;

public class CatsAndDogs {

public static void main(String[] args) {

List cats = new ArrayList();

for(int i = 0; i < 7; i++)

cats.add(new Cat(i));

// Not a problem to add a dog to cats:

cats.add(new Dog(7));

for(int i = 0; i < cats.size(); i++)

((Cat)cats.get(i)).id();

// Dog is detected only at run time

}

} ///:~The classes Cat and Dog are distinct; they have nothing in common except that they are Objects. (If you don’t explicitly say what class you’re inheriting from, you automatically inherit from Object.) Since ArrayList holds Objects, you can not only put Cat objects into this container using the ArrayList method add( ), but you can also add Dog objects without complaint at either compile time or run time. When you go to fetch out what you think are Cat objects using the ArrayList method get( ), you get back a reference to an object that you must cast to a Cat. Then you need to surround the entire expression with parentheses to force the evaluation of the cast before calling the id( ) method for Cat; otherwise, you’ll get a syntax error. Then, at run time, when you try to cast the Dog object to a Cat, you’ll get an exception. Feedback

This is more than just an annoyance. It’s something that can create difficult-to-find bugs. If one part (or several parts) of a program inserts objects into a container, and you discover only in a separate part of the program through an exception that a bad object was placed in the container, then you must find out where the bad insert occurred. Most of the time this isn’t a problem, but you should be aware of the possibility. Feedback

It turns out that in some cases things seem to work correctly without casting back to your original type. One case is quite special: The String class has some extra help from the compiler to make it work smoothly. Whenever the compiler expects a String object and it hasn’t got one, it will automatically call the toString( ) method that’s defined in Object and can be overridden by any Java class. This method produces the desired String object, which is then used wherever it is wanted. Feedback

Thus, all you need to do to make objects of your class print is to override the toString( ) method, as shown in the following example:

//: c11:Mouse.java

// Overriding toString().

public class Mouse {

private int mouseNumber;

public Mouse(int i) { mouseNumber = i; }

// Override Object.toString():

public String toString() {

return "This is Mouse #" + mouseNumber;

}

public int getNumber() { return mouseNumber; }

} ///:~//: c11:MouseTrap.java

public class MouseTrap {

static void caughtYa(Object m) {

Mouse mouse = (Mouse)m; // Cast from Object

System.out.println("Mouse: " + mouse.getNumber());

}

} ///:~//: c11:WorksAnyway.java

// In special cases, things just seem to work correctly.

import com.bruceeckel.simpletest.*;

import java.util.*;

public class WorksAnyway {

private static Test monitor = new Test();

public static void main(String[] args) {

List mice = new ArrayList();

for(int i = 0; i < 3; i++)

mice.add(new Mouse(i));

for(int i = 0; i < mice.size(); i++) {

// No cast necessary, automatic

// call to Object.toString():

System.out.println("Free mouse: " + mice.get(i));

MouseTrap.caughtYa(mice.get(i));

}

monitor.expect(new String[] {

"Free mouse: This is Mouse #0",

"Mouse: 0",

"Free mouse: This is Mouse #1",

"Mouse: 1",

"Free mouse: This is Mouse #2",

"Mouse: 2"

});

}

} ///:~You can see toString( ) overridden in Mouse. In the second for loop in main( ) you find the statement:

System.out.println("Free mouse: " + mice.get(i));After the ‘+’ sign the compiler expects to see a String object. get( ) produces an Object, so to get the desired String, the compiler implicitly calls toString( ). Unfortunately, you can work this kind of magic only with String; it isn’t available for any other type. Feedback

A second approach to hiding the cast has been placed inside MouseTrap. The caughtYa( ) method accepts not a Mouse, but an Object, which it then casts to a Mouse. This is quite presumptuous, of course, since by accepting an Object, anything could be passed to the method. However, if the cast is incorrect—if you passed the wrong type—you’ll get an exception at run time. This is not as good as compile-time checking, but it’s still robust. Note that in the use of this method:

MouseTrap.caughtYa(mice.get(i));

no cast is necessary. Feedback

You might not want to give up on this issue just yet. A more ironclad solution is to create a new class using the ArrayList, such that it will accept only your type and produce only your type:

//: c11:MouseList.java

// A type-conscious List.

import java.util.*;

public class MouseList {

private List list = new ArrayList();

public void add(Mouse m) { list.add(m); }

public Mouse get(int index) {

return (Mouse)list.get(index);

}

public int size() { return list.size(); }

} ///:~Here’s a test for the new container:

//: c11:MouseListTest.java

import com.bruceeckel.simpletest.*;

public class MouseListTest {

private static Test monitor = new Test();

public static void main(String[] args) {

MouseList mice = new MouseList();

for(int i = 0; i < 3; i++)

mice.add(new Mouse(i));

for(int i = 0; i < mice.size(); i++)

MouseTrap.caughtYa(mice.get(i));

monitor.expect(new String[] {

"Mouse: 0",

"Mouse: 1",

"Mouse: 2"

});

}

} ///:~This is similar to the previous example, except that the new MouseList class has a private member of type ArrayList and methods just like ArrayList. However, it doesn’t accept and produce generic Objects, only Mouse objects. Feedback

Note that if MouseList had instead been inherited from ArrayList, the add(Mouse) method would simply overload the existing add(Object), and there would still be no restriction on what type of objects could be added, and you wouldn’t get the desired results. Using composition, the MouseList simply uses the ArrayList, performing some activities before passing the responsibility for the rest of the operation on to the ArrayList. Feedback

Because a MouseList will accept only a Mouse, if you say:

mice.add(new Pigeon());

you will get an error message at compile time. This approach, while more tedious from a coding standpoint, will tell you immediately if you’re using a type improperly. Feedback

Note that no cast is necessary when using get( ); it’s always a Mouse. Feedback

This kind of problem isn’t isolated. There are numerous cases in which you need to create new types based on other types, and in which it is useful to have specific type information at compile time. This is the concept of a parameterized type. In C++, this is directly supported by the language using templates. It is likely that Java JDK 1.5 will provide generics, the Java version of parameterized types. Feedback

In any container class, you must have a way to put things in and a way to get things out. After all, that’s the primary job of a container—to hold things. In the ArrayList, add( ) is the way that you insert objects, and get( ) is one way to get things out. ArrayList is quite flexible; you can select anything at any time, and select multiple elements at once using different indexes. Feedback

If you want to start thinking at a higher level, there’s a drawback: You need to know the exact type of the container in order to use it. This might not seem bad at first, but what if you start out using an ArrayList, and later on you discover that because of the features you need in the container you actually need to use a Set instead? Or suppose you’d like to write a piece of generic code that doesn’t know or care what type of container it’s working with, so that it could be used on different types of containers without rewriting that code? Feedback

The concept of an iterator (yet another design pattern) can be used to achieve this abstraction. An iterator is an object whose job is to move through a sequence of objects and select each object in that sequence without the client programmer knowing or caring about the underlying structure of that sequence. In addition, an iterator is usually what’s called a “light-weight” object: one that’s cheap to create. For that reason, you’ll often find seemingly strange constraints for iterators; for example, some iterators can move in only one direction. Feedback

The Java Iterator is an example of an iterator with these kinds of constraints. There’s not much you can do with one except: Feedback

That’s all. It’s a simple implementation of an iterator, but still powerful (and there’s a more sophisticated ListIterator for Lists). To see how it works, let’s revisit the CatsAndDogs.java program from earlier in this chapter. In the original version, the method get( ) was used to select each element, but in the following modified version, an Iterator is used: Feedback

//: c11:CatsAndDogs2.java

// Simple container with Iterator.

package c11;

import com.bruceeckel.simpletest.*;

import java.util.*;

public class CatsAndDogs2 {

private static Test monitor = new Test();

public static void main(String[] args) {

List cats = new ArrayList();

for(int i = 0; i < 7; i++)

cats.add(new Cat(i));

Iterator e = cats.iterator();

while(e.hasNext())

((Cat)e.next()).id();

}

} ///:~You can see that the last few lines now use an Iterator to step through the sequence instead of a for loop. With the Iterator, you don’t need to worry about the number of elements in the container. That’s taken care of for you by hasNext( ) and next( ). Feedback

As another example, consider the creation of a general-purpose printing method:

//: c11:Printer.java

// Using an Iterator.